The Aesthetics of Erasure

2015

GUEST EDITORIAL STATEMENT

Paul Benzon

Temple University

Sarah Sweeney

Skidmore College

Erasure is the black hole at the center of digital culture, the endgame of cultural practice in the moment of network connectivity and cloud-based storage. Erasure has long been an important dimension of both artistic and critical work: Robert Rauschenberg asserted in an interview that his seminal 1953 Erased de Kooning Drawing was neither protest, nor destruction, nor vandalism, but rather poetry, the product of a deeply immanent engagement with the materiality and objecthood of preexisting work. [1] Similarly, for Jacques Derrida, the paradoxical status of all textual marks as perpetually under erasure (sous rature) is at the crux of the larger paradoxes of memory and forgetting, presence and absence, trace and destruction, that define the status of the archive. [2]

The work of Rauschenberg and Derrida, among others, makes clear that erasure is nothing new, that it is not unique to the moment of the digital, or indeed to any particular period of technology or artistic history – quite the opposite, we might say that as long as the human technology of mark-making has been in play, so has the possibility of erasure, the unmaking of the mark. Yet despite this longstanding possibility, the practice of erasure has taken on new meaning and relevance within a moment in which aesthetic and information materiality is newly at stake in a variety of contexts. In the early twenty-first century, we find ourselves in an era in which state surveillance is capable of capturing, storing, and analyzing all personal communications, and in which even the much-heralded ephemerality of photographic sharing applications such as Snapchat is revealed to be just another instance of deferred, secreted permanence. Within the context of such totalizing archival conditions, erasure seems all but impossible, an unattainable status amidst the constant hum of production, preservation, and sharing that defines contemporary digital knowledge work. Yet this near-impossibility is precisely what makes erasure a vitally necessary artistic, technological, and social practice. Erasure provides a point of departure from network culture, and thus from the constraints of big data, the archive, and the cloud; through erasure, forgetting and disappearance become radical, profoundly productive acts.

This special issue of Media-N brings together a diverse collection of visual and critical essays to consider the artistic, social, technological, and theoretical contours of this productivity. While our contributors explore practices of erasure that serve a range of social ends, from critique and liberation to state secrecy and violence, they all understand erasure as profoundly productive and generative, defined not by intangibility or absence but rather by eclectic moments of complexly situated, idiosyncratic materiality. Erasure takes place across a wide range of contexts and sites in these works: the state archive, the corporate server, the found document, the mass-market text. Within these contexts, our contributors reveal a variety of different marks within the larger practice of erasure. In a number of pieces, destruction serves as a governing operation, with authors and artists focusing on the technological eradication of texts by means of both chance and choice. Other contributors concentrate on overwriting as a practice of erasure, from the local context of a singular textual object to the global archive of the web at large. Concealment also emerges as a key strategy in a number of essays: as we learn to see what is covered against what is left uncovered, we learn to see these images as dense palimpsests, layered with history, memory, perception, and secrecy. Still others omit in order to create, raising the question of what is left out through what remains. Populated by traces, aftereffects, remainders, and residues as much as they are by invisibility, void, and blankness, these works collectively ask us to see and read in new ways, and to attend to the complex dynamics between absence and presence in coming to terms with the media art of the twenty-first century. As we read what has been taken against what is left, an array of larger issues and questions come into view as well, sites of inquiry that are made newly visible through the making-invisible of erasure.

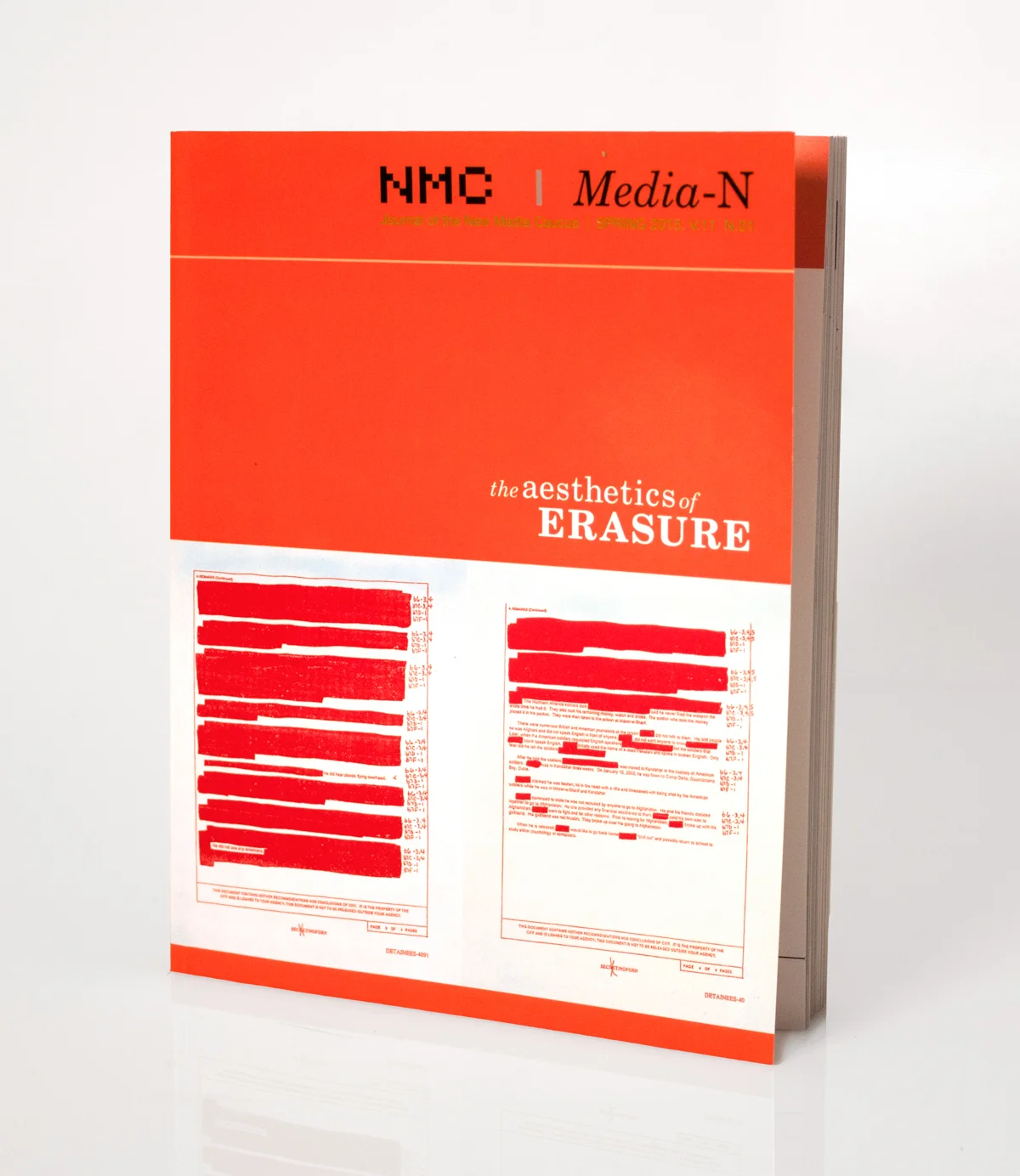

Our issue’s first section explores what erasure reveals about institutions of power and secrecy. Joshua Craze considers the Redaction Paintings and Dust Paintings, two recent series by Jenny Holzer that take redacted government documents from the War on Terror as their source material. Craze shows how Holzer’s transformation of these documents draws our attention to what he describes as their “negative equation” between the abstracting effects of state power and the concrete, embodied practices of discipline that sustain that power; as we see these documents with new eyes through Holzer’s appropriations, we see a secret history made public in their concealments and coverings. Seth Ellis’ visual essayVersion Control focuses on the public history that becomes visible through a single glitch in Google Street View. While the seemingly perpetual present moment that defines Street View comes from an equally perpetual erasure of the past through the overwriting of the present, this glitch reveals a more complex constellation of space and time that lies remnant within the digital behemoth’s archive. Seizing on the stratified, multiple pasts revealed by this glitch as an artistic point of departure, Ellis engages in a speculative reimagining of public space and the social populations and possibilities that might inhabit it.

In our second section, Kaja Marczewska and Justin Berry consider how artistic practices of erasure serve as a means of critique within the excess of late capital culture. Like Ellis, Marczewska focuses on Google, turning her attention to the corporation’s practices of data mining and user profiling. Her essay focuses on Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff’s conceptual novel American Psycho, in which the authors reproduce Bret Easton Ellis’ novel of the same name as a nearly blank text, omitting Ellis’ prose and instead printing only the Google Ads generated by sending that prose back and forth through Gmail. This practice transforms the infamous violence and material excess of the original text in order to foreground the strategic possibilities of Marczewska’s titular “algorithmic extreme,” suggesting how in a moment defined by the invisible violence and excess of big data, a text stripped of everything but that data’s end product constitutes perhaps both the purest document of digital capitalism and the sharpest critique of that capitalism. Likewise, Justin Berry’s seriesUntitling Landscapes digitally paints over the identifying information from the covers of mass-market science fiction and fantasy paperbacks, replacing it with imperceptibly integrated blank space. The resulting landscapes signify in their emptiness for imagined safe zones, silent refuges from the cultural and visual noise of late capital.

Taking the relations between information and sensation as a point of departure, the artists in our third section focus on how erasure modulates between signal and noise, and on the roles omission and concealment might play in how we see and read. In Habits of Experience, Habits of Understanding, David Gyscek paints over portions of a photographed landscape, concealing different components of each image across this series to create a constant oscillation between figure and ground over multiple images. For Gyscek, this approach juxtaposes the encyclopedic capture of the camera and the selective perceptions of the embodied seer; by “imagining out” the comprehensive data of the photographic image, he transforms the truth claims of the modern era’s most crucial visual technology, creating spaces that are subject to the subtraction and selectivity of the human mind. Derek Beaulieu’s experimental novel Local Colour also operates through visual subtraction: using Paul Auster’s novella Ghosts as source material, Beaulieu removes all of Auster’s text except for color-oriented, chromatic words, and then replaces those words with rectangles corresponding to the colors they denote. Stripped of all alphabetic markers and identifiers, the resulting text hovers between poetry, art, and sound, an ambient artifact that throws into relief the profoundly material modes of filtering that define all of these forms.

While technology and technological change are at stake in all of the work in this special issue, the artists and writers in our fourth section foreground these issues with particular urgency. The Deletionist, a JavaScript bookmarklet developed by Amaranth Borsuk, Jesper Juul, and Nick Montfort, generates erasure poetry from the text of any web page. The deeply spatial texts that result derive not from randomized erasures but rather from highly formalized rules, producing the poetry of emptiness through algorithmic constraint. The Deletionist’s creators see it as revealing an alternate World Wide Web – a “Worl,” in their nomenclature – that is as distinctive and different as it is fugitive. Torsa Ghosal’s discussion of worlds under erasure in contemporary Hollywood cinema strikes a similar technological resonance along the axes of time and media change. The erasure of imagined storyworlds has been a common strategy of literary experimentation for decades, but in transposing this practice to the visual, Ghosal finds an explanation for this practice rooted in medium specificity rather than narrative practice. Tracing this erasure – a practice she terms “unprojection” – across a series of recent films, she shows how it becomes a testing ground on which filmmakers represent and respond to the change from analog to digital cinema, interrogating the stakes of technological change through their films’ aesthetic frameworks. William Basinski’s ambient composition The Disintegration Loops also self-reflexively documents this change through a similarly haunting, dramatic destruction. Basinski produced The Disintegration Loops by digitizing a set of fragile analog tape loops, documenting the sounds of decay produced as the tapes began to fall apart in the process of transcription. Coupled with the composer’s video of the World Trade Center towers collapsing – an event that took place as Basinski finished transcribing the tapes – these sounds document change through decay, hauntingly transposing one materiality into another.

Our issue ends with several essays that turn explicitly to the question of the archive, perhaps the largest and most fundamental issue at stake in the aesthetics of erasure. The materiality that runs through erasure in all its forms bears on the archive in complex, accretive ways; if every act of erasure is an act of production, a generative mark, then every erasure thus adds to the archive at the same time that it seems to take away from it. Ella Klik and Diana Kamin discuss Max Dean’s 1992-1995 installation As Yet Untitled, a predigital work in which a robotic arm presents viewers with found photographs to be saved or shredded, as part of a complex genealogy of the role of erasure within the digital archive. Offering a counterpoint to several critical accounts of digital erasure, Klik and Kamin use Dean’s work as the cornerstone of a theory of the lost/found, a third archival gesture beyond the binary of saving and deleting. Beyond these two endpoints, they suggest, the lost/found poses the possibility of a more immanent and incomplete trajectory for archival objects, characterized by moments of “producing, dislocating, finding, and re-purposing that ha[ve] already taken place and [are] yet to come.” In reading the protocols of digital storage alongside Sigmund Freud’s archetypal Mystic Writing-Pad, Matthew Schilleman traces a similar liminality between preservation and disposal. Tracing a history of digital reading and writing from Vannevar Bush’s prototypical memex to contemporary storage software such as Evernote, Schilleman shows how the tension between remembering and repressing is not only psychological but also technological, with digital technology’s perpetual promise of renewal and refreshability inextricable from its need to erase. Schilleman sees in this interdependence a powerful need to introduce forgetting into discussions of digital media – to remember forgetting, as it were.

Taken together, the investigations into the place of erasure in twenty-first-century art, technology, and culture in this special issue reveal a wide topography of locations, processes, aesthetics, and intentionalities. They attest to the ways in which, in its complexities, its materialities, and its mobilities across time, space, and medium, erasure is an urgently present artistic practice, now perhaps more than ever. When we look at an erasure, we see a text that is neither less nor more than its original source, but rather one that is uncannily elsewhere. Indeed, perhaps in looking at erasures such as the ones in this collection, we are compelled to look not at a single site of disappearance, but ultimately at everything and everywhere else—to take the additive, generative, productive aesthetics of erasure as a catalyst for seeing the complex networks, affiliations, appropriations, histories, and futures that exist in ever-changing configurations around the voids of the digital moment.

ReferencesBios

Paul Benzon teaches media studies, contemporary literature and culture, and critical writing at Temple University. In his research, he explores how the material and formal extremities of textual artifacts reveal the cultural history of modern and contemporary media technology. He is currently at work on a book project entitled Deletions: Absence, Obsolescence, and the Ends of Media. In Deletions, he traces a history of textual disappearance across a range of twentieth- and twenty-first-century media, from book burning, redaction, and the spontaneous combustion of celluloid film to the global circulation of electronic waste and the imminent obsolescence of physical storage media amidst the twenty-first-century rhetoric of the digital cloud. His work has appeared in electronic book review, CLCWeb, PMLA (where it won the William Riley Parker Prize for an Outstanding Article in 2010), and Narrative (where it received the James Phelan Prize for the Best Contribution to Narrative in 2013), and is forthcoming in The Routledge Companion to Media Studies and Digital Humanities (2016) and Publishing as Artistic Practice (2016).

Sarah Sweeney received her BA in Studio Art from Williams College and an MFA in Digital Media from Columbia University School of the Arts and is currently an Associate Professor of Art at Skidmore College. Her digital and interactive work interrogates the relationship between photographic memory objects and physical memories, and is informed by both the study of memory science and the history of documentary technologies. In her work, she explores the space between information that is stored corporeally in our memory and the information that is captured and stored in memory objects created by documentary technologies including camera phones, stereoscopic cameras, and home video cameras – each project makes tangible the deletions and accretions produced through our interactions with these technologies. She is the creator of The Forgetting Machine, an iPhone app commissioned by the new media organization Rhizome, that systematically destroys digital photographs each time they are viewed or refreshed to simulate the theory of reconsolidation proposed by scientists studying memory. Her work has appeared nationally and internationally in exhibitions at locations including the Orange County Center for Contemporary Art, the Los Angeles Center for Digital Art, the New Jersey State Museum, the Black and White Gallery, and the UCR/California Photography Museum.

- Robert Rauschenberg, interview, “Robert Rauschenberg discusses Erased de Kooning Drawing,” Artforum, http://artforum.com/video/id=19778&mode=large, accessed March 22, 2015.

- The questions of erasure, trace, and the archive are pervasive in Derrida’s work; see, for example, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).